Ingrid Therwath, journaliste et politologue franco-indienne, lesbienne et membre de l’AJL, décrit, dans un texte écrit en anglais et à la première personne, l’importance de la décision de la Cour suprême de dépénaliser l’homosexualité.

Ingrid Therwath, journaliste et politologue franco-indienne, lesbienne et membre de l’AJL, décrit, dans un texte écrit en anglais et à la première personne, l’importance de la décision de la Cour suprême de dépénaliser l’homosexualité.

It was a foggy afternoon in Delhi. I was, at the time, writing a book on the internet and its uses in India and had decided –for this research as well as for personal reasons— to attend the Delhi Queer Pride. The event had been started in 2008, a year before the Delhi high Court decided to do away with section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (the judgement was overthrown later). By the time, the Delhi Queer Pride 2011 was held, article 377 as very much back in force.

The article 377, which dates from 1861, criminalized intercourse “against nature”, a Victorian expression used to refer to anal sex. It made the public (or even private for that matter) expression of consensual, adult, same-sex love a felony. And homosexuality in India was punishable by up to life in prison.

The 2011 Delhi Queer Pride was a moment of pride and joy but fear was palpable on the street. The police officers on duty at the venue made many of us uneasy as to whether they were present for our protection or on the contrary for our imminent arrest.

The organisers had been very clear on Facebook, where the gathering was being organised: you can – and probably should – come in “civilian clothes” (i.e. in your ordinary outfits), masks and signs will be provided on the spot if needed. The idea was to protect the participants’ identity for fear of homophobia… and legal pursuits. Predictably, a large number of persons, children in the picture below but mostly adults in the crowd were wearing masks.

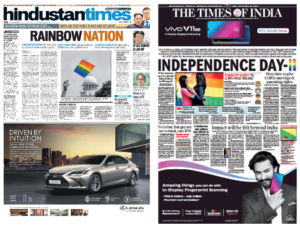

On the 6th of September 2018, the Supreme Court of India overthrew section 377 of the Indian penal code, a decision that will have a direct impact of the lives of millions of LGBT person. As soon as the verdict was pronounced thousands and thousands of lesbians and gays thronged the streets of small cities and metropolises to express their joy. Most of them did need to wear masks. They will not need to anymore, at least not for fear of the law.

The freedom to love regardless of one’s sexual orientation is a defining moment in the history of India

The 6th of September 2018 will be remembered as an important date in the history of LGBT rights in India, of minorities’ rights in India, of democratic institutions and of the struggle towards equality in the world at large, particularly in the rest of the Commonwealth, where similar colonial provisions are still being implemented. Nothing less. This is by no means the delusional impression of a relieved activist. This is, on the contrary, an analysis derived from a close scrutiny of the 495 pages long verdict that unanimously repealed the article 377.

Obviously, the police violence, particularly against gay men, their deliberate targeting and harassment, will not immediately stop and the large and unfortunate discrepancy between the law and its actual implementation is bound to go on. But the vindication of the freedom to love and be loved regardless of one’s gender or sexual orientation will still be a defining moment in the history of the country. It vindicates the right to love and the pursuit of happiness as fundamental rights, irrespective of particularisms.

This verdict will not only change the lives of Indian LGBTs by giving them a sense of pride, equality, but it also defends a certain idea of India, one that is not based on the current government’s nefarious vision of democracy as a majoritarian dictatorship or even as a mobocracy. The five judges have pointed that democracy is best measured by the protection and equality given to weaker or smaller sections of society and not by the imposition of the sentiments or morality of the larger group onto minorities. This resonates politically not only in India but in many established Western democracies too.

The impact of Indian – and foreign – journalists

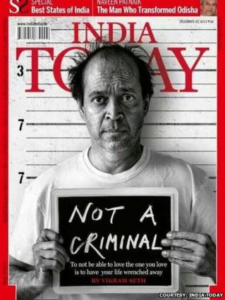

On the 6th of September 2018, social media, particularly Twitter, which has over the years become infamous in India for its hordes of extreme-right, Hindu fundamentalist trolls, have been inundated by pro-LGBT memes, comments articles. And, many journalists and public commentators have circulated a five-year old front page of the weekly magazine India Today. This frontpage shows the acclaimed poet and writer Vikram Seth in a staged mugshot picture holding a sign that reads “not a criminal”. The issue was the very first one of a leading publication to defend LGBT rights and illustrates the impact journalists can have over the years not merely in holding a mirror to the face of society but in contributing to the debates and actually shaping public opinion while using facts and personal accounts as opposed to propaganda and religious or moral diktats.

On the 6th of September 2018, the Indian media was particularly attentive at the way this news was being covered outside the country, particularly in the USA and in the UK. The scrutiny of British media organisations in particular is very significant. The website of Zee TV for example foregrounded the celebratory mood of the Washington Post, the New York Times, the BBC and the Guardian.

Indeed, it seems that Indian journalists found a validation of their own treatment (interviewing the cheering crows, the LGBT lawyers who were heard by the Supreme Court, etc) thanks to the positive outlook of the British journalists and the British news outlets, in an ironic historical twist. Indeed, Indian journalists found a validation and an encouragement in the post-colonial treatment of the repeal of a legal provision instituted during the colonial era. The positive coverage of the global press strengthens and legitimizes the coverage of celebrations in India itself, which only points out to the importance of a fair and respectful treatment of LGBT issues around the world. Similarly, French journalist should keep this in mind when they cover the news in countries that were formerly colonized by France. They bear a responsibility towards their audience beyond the limit of national borders and can have an impact on the way the information and the people are treated.

Finally, Justice Indu Malhotra said that “history owes an apology to members of the community for the delay in ensuring their rights”. The nationalist argument against article 377 as a remnant of the colonial past that had nothing to do with contemporary India is flawed : after all, India had 71 years since its independence to do away with a Victorian provision. Homophobia is an ugly Indian truth too. Many years ago, I sat down inside the office of a leading psychiatrist in Delhi. I was distressed. I came out to him. He listened without much emotion transpiring from his face while I was recounting my coming to terms with my homosexuality and its many implications for my family. When I was done, he suggested a course of electrical shocks to cure me. He added: “this is not really done so much now. But, beta (my child), the best is you take all the medicine I will prescribe. You will have no more pain. You will simply not feel at all. This is the only solution”. This sounded like a death sentence. Somehow, this doctor had the law on his side. Not any more.

History does owe the LBGT community an apology, so does the successive Indian governments, many police officers, many doctors and even many members of our own families. The 6th of September 2018 Supreme Court verdict constitutes a very big step but the road to complete equality and freedom is still very long. When India became independent, on the stroke of midnight of the 15 of August 1947, its first Prime minister famously said “long years ago, we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially”.

The repeal of section 377 is XXIth century India’s new tryst with destiny. While the mood is celebratory both in the media and on the streets, the time will soon come to redeem our pledge. And very substantially.